Background

Depression after Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) is the most common psychological condition, and its occurrence is substantially higher than among people with general medical conditions. Based on a meta-analysis, depression is prevalent among one-fourth of the survivors of SCI (Williams & Murray, 2015). Furthermore, although depressive symptoms may occur in the adjustment process after SCI (Dorsett et al., 2017), there are increased reports of self-harm and suicidal behavior among people with depression (Kennedy & Garmon-Jones, 2017). Additionally, depression was associated with lower quality of life among SCI survivors (Tate et al., 2015). Hence, early identification of depressive symptoms and their management is crucial.

A self-management approach is increasingly becoming popular in chronic health conditions, but it is less explored in depressive symptoms management due to merely focusing on the management of acute symptoms with medications or traditional psychotherapies (Duggal, 2019). Individuals with SCI utilize a wide range of management strategies for depressive moods. It was found that individuals with SCI preferred an exercise program followed by antidepressant medications and counseling programs to reduce depression (Fann et al., 2013). Clinical trials conducted in Australia and Canada reported the use of cognitive-behavioral therapies (Craig et al., 2017) with no effect in decreasing depressive symptoms. In contrast, specialized yoga sessions (Curtis et al., 2017) and online mindfulness and psychoeducation (Hearn & Finlay, 2018) significantly reduced depressive mood.

Several factors, including personal, health and illness, and environment, influence an individual’s perception in symptom experience and management (Dodd et al., 2001). Although previous studies contributed knowledge to the understanding of depressive mood and its management in people with SCI, these studies were conducted primarily in high-income countries (Cadel et al., 2020; Craig et al., 2017; Hearn & Finlay, 2018; Khazaeipour et al., 2015; Tzanos et al., 2018). Gaps of knowledge still exist in low-and middle-income countries like Nepal. Not only does the socioeconomic environment differ, but also striking differences exist within the culture, healthcare services, and physical environment. For instance, Nepal is predominantly a Hindu country, and most Hindus believe in Karma—wrong deeds committed in the past—as a cause of serious illness and suffering in life (Wilson, 2019). In addition, the high cost of medical expenses results in the practice of people seeking traditional methods to manage their health problems. In addition, the large areas of mountainous regions and the lack of wheelchair-accessible transportation are common challenges in Nepal. There is a lack of trained health professionals to provide mental health services in rural areas. Therefore, the previous findings may not be generalizable to the context of depressive mood occurrence and self-management among Nepalese people with SCI.

Specific to Nepal, no study has explored depressive mood self-management among community dwellers with SCI. Therefore, this study aimed to identify depressive mood prevalence and severity and its management strategies among people with SCI living in the community. The results of this study will provide essential information for nurses and healthcare professionals to plan for early identification and management of depressive mood among community-dwelling people with SCI in low-and middle-income countries like Nepal.

Methods

Study Design

A descriptive study was employed in this study.

Participants

The study was conducted in the 13 districts of Bagmati Province of Nepal. The inclusion criteria to select participants were: (1) aged 18 years or older, (2) living in the community for 3-12 months post-discharge from three health centers, and (3) being able to communicate in the Nepali language. The three health centers were: (1) the Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital (TUTH), (2) the National Trauma Center (NTC), a government-owned trauma hospital, and (3) the Spinal Injury Rehabilitation Center (SIRC), the largest spinal rehabilitation center and a non-government organization.

The sample was drawn from the target population of 490 people with SCI living in the communities in 2018. The estimated sample size was calculated using the proportion percentage with a level of confidence of 95% and an acceptable margin for random error (Kasiulevicius et al., 2006). From previous studies, the estimated proportion of depression in people with SCI was about 45% (Khazaeipour et al., 2015; Rahnama et al., 2015). Thus, the calculated sample size in this study was 115. The sample was then drawn using a stratified random sampling technique. Hence, the numbers of participants for data collection from the TUTH, NTC, and SIRC facilities were 18, 21, and 76 cases, respectively.

Instruments

The research instruments consisted of the following questionnaires:

Demographics, Health and Illness, and Environment Data Form. This questionnaire consisted of closed-ended questions including age, gender, religion, education, employment status, monthly income, duration of injury, type of paralysis, pain intensity, physical complications, place of residence, and functional dependency level.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9, Nepali version (Bhattarai et al., 2018) was used to assess the severity of depressive mood after permission from the original authors. PHQ-9 is widely used among the SCI population (Bombardier et al., 2012; Fann et al., 2013; Tzanos et al., 2018). Each item response in the tool was reported on a 4-point Likert scale of 0 = not at all to 3 = nearly every day. The total score of the PHQ-9 ranges from 0 to 27, where the higher score represents a higher depressive mood. The tool has good reliability, validity, and diagnostic accuracy compared to the DSM-IV MDD criteria (Sun et al., 2020). Internal consistency of this tool demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.79 in this study.

Depressive Mood Management Questionnaire (DMMQ). The DMMQ consisted of four questions that were modified from the studies of Dodd et al. (2001) and (Fann et al., 2013). Two open-ended questions were as follows; (i) type of management approach, “what management methods they used to reduce depressive mood” and (ii) reason for using the approach “why did they use those methods”. Two closed-ended questions composed of (i) frequency of using the method “how often” which the responses were categorized into three levels, i.e., “rarely”, “often”, and “always” and (ii) effectiveness of the method “how effective” where the responses were categorized into five levels, i.e., “worsening effect”, “no effect”, “slightly better”, “much better”, and “completely resolved”. In addition, the participants were asked about the use of depressive mood management approaches within the previous one month. The contents, congruence, and appropriateness of DMMQ were validated by five SCI experts in Nepal, including (1) an orthopedic nurse lecturer, (2) a senior SCI nurse, (3) a rehabilitation physician, (4) a neurosurgeon, and (5) a physiotherapist. The content validity index of DMMQ was 1.00. The DMMQ was then piloted with 15 sample people with SCI in another setting prior to data collection.

Data Collection

After receiving permission from the ethical committee in each hospital, a list of names and contact numbers were obtained from the medical record departments. The first researcher then contacted possible participants by telephone. Upon meeting the inclusion criteria, the first researcher set a meeting with participants in person. Willing participants or a designated family member provided written informed consent. Following enrollment, the researcher provided written questionnaires or conducted an interview with participants based on their preferences and literacy. The PHQ-9, Nepali version, and the DMMQ were conducted in the Nepali language by the first author, who was a Nepalese Master’s student. The data collection was done from March to May 2019 using multiple methods, including self-report and interview, requiring a time duration of 15-20 minutes. During the data collection, some problems were encountered by the researcher. Since the interviews were conducted at the participant’s home, sometimes they were busy with household work, requiring the researcher to wait for long periods. In addition, at many visits, some curious neighbors tried to join the interview process, which distracted the researcher and the participant. The researcher had to stop the interview, counsel participants and neighbors, and start again when this occurred.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including frequency, percentage, and mean and standard deviation, were used to present depressive mood. In addition, a quantitative content analysis was done to analyze the data from the open-ended questions of depressive management (White & Marsh, 2006). The steps of quantitative content analysis involve identifying appropriate data, establishing a unit of analysis and coding categories, and coding data. After the coding, the researchers checked coding validity and reliability, analyzed and grouped the coded data, and applied descriptive statistics (i.e., frequency counts and percentages) to present the findings.

Ethical Considerations

The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Nursing, Prince of Songkla University, Thailand (2018 NSt -Qn 062) and the Nepal Health Research Council (Ref. No. 2182), Spinal Injury Rehabilitation Center (Ref. No. 88/075/076), Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital (Ref. No. 21/03/2019), and National Trauma Center (Ref. No. 14/02/2019). Written informed consent was obtained from the participants. For individuals unable to read and write, the researcher read out the participant information sheet to the potential participants, and a written consent form was provided by their family caregiver. Anonymity and confidentiality of the participants were maintained throughout the study.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 115 people with SCI were enrolled for data collection from the 13 districts of Bagmati Province. The demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. More than half were male (n = 67, 58.3%), Hindus (n = 84, 73.0%), and lived in rural areas (n = 82, 71.3%). The vast majority of individuals had paraplegia (n = 92, 80.0%) and had physical complications (n = 102, 88.7%). The pain was experienced by all participants with an average moderate level. The most common level of dependency was moderate (n = 46, 40.0%).

| Characteristics | N (%) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 32.5 (9.4) | |

| 18‒30 | 58 (50.4) | |

| 31‒45 | 47 (40.9) | |

| 46‒57 | 10 (8.7) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 67 (58.3) | |

| Female | 48 (41.7) | |

| Religion | ||

| Hindu | 84 (73.0) | |

| Others (Buddhist and Christian) | 31 (27.0) | |

| Place of residence | ||

| Urban | 33 (28.7) | |

| Rural | 82 (71.3) | |

| Education, years | 8.5 (4.2) | |

| Occupation before SCI | ||

| Unemployed (student, housewife) | 33 (28.7) | |

| Employed | 82 (71.3) | |

| Occupation after SCI | ||

| Unemployed | 69 (60.0) | |

| Employed | 46 (40.0) | |

| Family monthly income, NPR (1 USD = 117 NPR) | ||

| ≤30,000 | 82 (71.3) | |

| >30,000 | 33 (28.7) | |

| Duration of injury, months | 12.4 (3.7) | |

| Living in the community, months | ||

| 3‒6 | 10 (8.7) | |

| 7‒9 | 53 (46.1) | |

| 10‒12 | 52 (45.2) | |

| Home medications after hospital discharge | ||

| No | 92 (80.0) | |

| Yes (i.e., Amitriptyline, Imipramine, Escitalopram, Clonazepam) | 23 (20.0) | |

| Type of paralysis | ||

| Paraplegia | 92 (80.0) | |

| Tetraplegia | 23 (20.0) | |

| Pain intensity | 5.3 (1.4) | |

| Physical complications | ||

| No | 13 (11.3) | |

| Yesa (constipation, pressure ulcer, UTI) | 102 (88.7) | |

| Functional dependency levelb | ||

| Complete (0‒24) | 11 (9.6) | |

| High (25‒49) | 23 (20.0) | |

| Moderate (50‒74) | 46 (40.0) | |

| Minimal (75‒90) | 32 (27.8) | |

| Independent (91‒100) | 3 (2.6) |

Depressive Mood Prevalence and Severity

Ninety-seven cases (84.3%) had a depressive mood. Of these, the mean (SD) score of depressive mood severity was at a moderate level of 11.0 (4.2) (Table 2).

| The severity of depressive mood (scores) | N = 115 | Mean (SD) | Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| None (0‒4) | 18 (15.7) | ||

| Yes (5-27) | 97 (84.3) | 11.0 (4.2) | Moderate |

| Mild (5‒9) | 38 (39.2) | ||

| Moderate (10‒14) | 35 (36.1) | ||

| Moderately severe (15‒19) | 21 (21.6) | ||

| Severe (20‒27) | 3 (3.1) |

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

SD: standard deviation

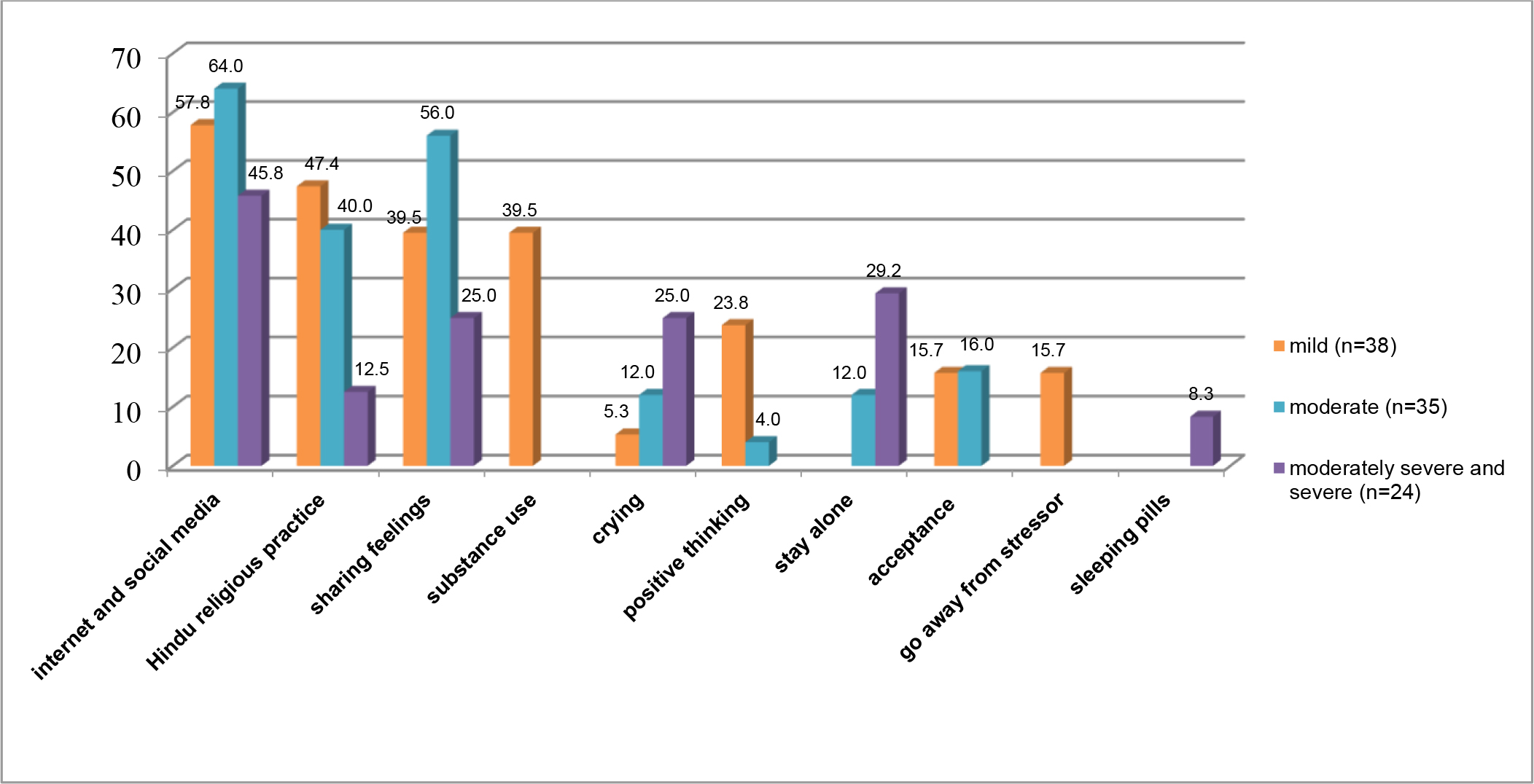

Self-Management of Depressive Mood

Of the 97 individuals who experienced depressive moods, all of them commonly used non-pharmacological methods for self-management. The five most common methods were: (1) using internet and social media (n = 49, 50.5%), (2) sharing feelings (e.g., with family members, friends, and peer group) (n = 31, 31.9%), (3) Hindu religious practices (n = 31, 31.9%), (4) substance abuse (e.g., alcohol, cannabis) (n = 15, 15.5%), and (5) crying (n = 11, 11.3%). The percentage of depressive mood management methods used by participants was based on the severity of depressive mood (Figure 1).

The most common reasons for using the methods of depressive mood management were easy to use and feeling of relaxation (e.g., sharing feelings and internet and social media) (30.9%), peaceful mind and decreased suffering (e.g., religious practice) (20.6%), and find no other ways to provide comfort (e.g., accepting, crying) (20.6%) (Table 3).

| Reasons for depressive mood managementa | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Relaxation and easy to use (e.g., internet and social media, sharing feelings) | 30 (30.9) |

| Reduce depressive mood and suffering and promote peaceful mind (e.g., religious practice) | 20 (20.6) |

| Find no other ways to provide comfort (e.g., accepting, crying, going away from stressors, staying alone) | 20 (20.6) |

| Reduce effects of bad luck and evil eyes (e.g., praying, worshipping) | 18 (18.5) |

| Have multiple effects such as peaceful mind and relaxation (e.g., meditation, substance abuse) | 12 (12.4) |

In addition, among those who “often” used sharing feelings (n = 18, 58.1%) to decrease their depressive mood, most individuals reported their depressive mood “completely disappeared” (n = 15, 48.4%). The effectiveness of internet and social media use and Hindu religious practices were also demonstrated as several participants rated their depressive mood as “much better” (n = 26, 53.1% and n = 13,42.0 %, respectively) after they “often to always” applied these methods (n = 27, 55.1% and n = 19,61.2 %, respectively) to relieve their symptom (Table 4).

| Depressive mood management a | Frequency of use | Effectiveness | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rarely | Often | Always | Worsening Effect | No effect | Slightly better | Much better | Completely resolved | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Pharmacological approach (n = 2, 2.1%) | ||||||||

| Sleeping pills/name unknown | 2 (100.0) | - | - | - | - | 2 (100.0) | - | - |

| Non-pharmacological approaches (n = 97, 100%) | ||||||||

| Using the internet and social media (n = 49, 50.5%) | 4 (8.2) | 18 (36.7) | 27 (55.1) | - | - | 9 (18.4) | 26 (53.1) | 14 (28.5) |

| Share feelings (n = 31, 31.9%) | 3 (9.6) | 18 (58.1) | 10 (32.3) | - | - | 6 (19.3) | 10 (32.2) | 15 (48.4) |

| Hindu religious practices (e.g., praying, worshipping ‘Puja’, ‘Graha Shanti’, ‘Bhakal’ (n = 31, 31.9%) | 4 (13.0) | 19 (61.2) | 8 (25.8) | - | 5 (16.0) | 9 (29.0) | 13 (42.0) | 4 (13.0) |

| Substance abuse (n = 15, 15.5%) | 3 (20.0) | 7 (46.7) | 5 (33.3) | - | - | 2 (13.3) | 8 (53.3) | 5 (33.3) |

| Accepting (n =12, 12.4%) | - | 12 (100.0) | - | - | - | 4 (33.3) | 6 (50.0) | 2 (16.7) |

| Crying (n =11, 11.3%) | - | 11 (100.0) | - | 2 (18.2) | 2 (18.2) | 2 (18.2) | 5 (45.4) | - |

| Positive thinking (n =10, 10.3%) | - | 10 (100.0) | - | - | - | 2 (20.0) | 8 (80.0) | - |

| Staying alone (n = 8, 8.2%) | - | 8 (100.0) | - | - | - | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | - |

| Going away from the stressor (n = 6, 6.2%) | - | 6 (100.0) | - | - | - | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | - |

Moreover, the groups of participants with moderately severe to severe depressive mood used self-management that was quite different from other groups to reduce depressive mood. They used the internet and social media (n = 11, 45.8%), staying alone (n = 7, 29.2%), crying (n = 6, 25.0%), sharing feelings (n = 6, 25.0%), and Hindu religious practice (n = 3, 12.5%). Few participants (n = 2, 8.3%) used sleep-inducing medications of unknown names without prescription (Figure 1).

Discussion

The findings of this study showed that most people with SCI had depressive mood, and its average severity score was at a moderate level, for which they predominantly used non-pharmacological approaches.

The prevalence and severity of depressive mood among Nepalese patients with SCI were higher than reported in previous studies (Al Abbudi et al., 2017; Khazaeipour et al., 2015). These results may be related to physical illness and complications and a lack of self-management skills among people with SCI. In addition, other reasons could be, short duration after SCI (Munce et al., 2016; Tzanos et al., 2018), functional dependence (Khazaeipour et al., 2015), pain and physical complications (Craig et al., 2017; Tzanos et al., 2018), and focusing on non-pharmacological approaches.

Participants in this study predominantly used non-pharmacological measures to manage depressive moods because they are easy to use. Moreover, most of them lived in rural areas, often several hours from roads with vehicle access. At least two people must carry people with SCI in these areas to reach the nearest health facility, which generally occurs only during medical emergencies.

In addition, being a predominately Hindu country, the Nepalese believe that pain or suffering is caused by transgressions of the past, or Karma (Wilson, 2019). This belief can contribute to individuals not accessing medical help for psychological problems. Hence, individuals used mostly a distraction, sharing of feelings, and spiritual/religious belief approaches to manage their depressive mood.

Using the internet as a diversion was commonly used by the participants in this study. This was possible because it is easy to use as a hobby. Internet use was significantly associated with reduced depression compared to non-users. Specifically, daily internet users had less probability of developing depressive symptoms (Tsai et al., 2014). In addition, people with SCI shared their feelings with their family and peer group and through social media in the form of poems, songs, and maintaining diaries. According to the participants in this study, distraction and sharing feelings with others helped them improve their mood, which could be due to the release of chemicals such as serotonin and endorphins; a similar finding was reported in a previous study (Searle et al., 2011). Likewise, involvement in such pleasurable activities may help to improve psychological functioning.

Individuals in this study regularly used Hindu religious management, including “Puja” and “Graha Shanti” (worshiping God to remove bad luck and evil eyes) and “Bhakal” (promises to God for a special offering). These practices are common because they believe that God gives them strength to deal with difficult situations in life and strengthens their inner power to keep them moving forward in life and provide peace of mind, which was also consistent with past findings (Duggan et al., 2016; Xue et al., 2016). Some believe that their current situation is like an examination or a punishment from a higher power (God). Religious and spiritual approaches are used widely as part of a coping process by individuals living with chronic health conditions (Rahnama et al., 2015). In a developing country like Nepal, where basic health needs are not met, nurses can plan to model spiritual practices and approaches to improve psychological health and assist in the rehabilitation process.

Substance abuse, including drinking alcohol and smoking cannabis, was reported by individuals with mild depressive moods because it was easily available to them from their friends. In addition, all participants had pain, and many had secondary complications that possibly elevated depressive mood symptoms (Tzanos et al., 2018). Therefore, they reported that drinking alcohol and use of cannabis helped to reduce neuropathic pain (Bourke et al., 2019), improved sleep, and decreased negative feelings and thoughts (Hawley et al., 2018; Kosiba et al., 2019). However, substance abuse is considered a maladaptive coping strategy that can lead to poor emotional control (Heffer & Willoughby, 2017). Hence, health professionals should discourage such practices

In addition, participants with moderately severe and severe depressive mood symptoms reported crying and staying alone to release their inner feelings of sadness while in a depressive mood. Few participants used unprescribed sleep-inducing medications to forget depressive feelings, which should also be discouraged in any case.

This study was conducted in a single province of Nepal with a limited sample size; therefore, replication of this study with larger sample size and in other settings is necessary.

Limitation of the Study

Although this study was conducted in many districts of Bagmati province, the findings may not be generalizable to all individuals with SCI living in Nepal.

Conclusion

Depressive mood was highly prevalent among individuals with SCI living in the community in Nepal during the first year following initial hospitalization. However, most individuals perceived that depressive mood effectively disappeared when sharing feelings with family members as a self-management technique. Therefore, nurses and other health professionals should provide psychoeducation for individuals with SCI and their family members to recognize symptoms of depressed mood and better support mental well-being, either during their stay at the health center or using social media platforms after discharge. Moreover, most individuals with SCI in our study live in rural settings that have transportation barriers to engage in social activities and access healthcare services. Therefore, addressing these barriers is warranted to better identify and treat depressive moods among individuals with SCI.