Background

There is a steep increase in the number of older persons worldwide; however, the number of older persons with memory loss in middle-income countries in Asia is projected to increase dramatically (Hinton et al., 2019). In Asian countries, particularly Thailand, older adults with mild to severe dementia reside at home. However, older adults with moderate to severe dementia are cared for by a family caregiver and receive care with activity daily living services from a community long-term care facility integrated with the primary healthcare system (Chuakhamfoo et al., 2020). Individuals with dementia generally have memory and cognitive impairments that result in the decline of their abilities and functioning. These also cause an increase in neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPs). Family caregivers experience several challenges in providing dementia care, especially those of older adults with moderate dementia who reported severe distress (Chuakhamfoo et al., 2020). Caregivers have to manage NPs of the care recipients such as agitation and aggression, anxiety, delusions and hallucination, and nighttime wandering. Also, family caregivers have to provide both visible and invisible care to their care recipients, such as assisting with personal care, processing financial transactions, giving advice, and protecting the care recipients (Chuakhamfoo et al., 2020).

Caregiving for individuals with dementia could generate higher stress, in which caregivers experience personal health problems and social isolation, increasing negative feelings toward the care recipient (Lindeza et al., 2020). Caregivers of older adults with dementia described feelings of anger, sadness, or guilt due to the duration of care hours and the difficulty of managing the NPs of the care recipient (Bursch & Butcher, 2012). Physical strains of caregivers for older adults are reported, and this is partially resulted from a lack of social support (Wang et al., 2018). When family caregivers cannot balance the work, they are distressed in the family relationships, roles, and finances which can be manifested in job-related problems (Bachmann, 2020; Ornstein & Gaugler, 2012). Exposure to continued stressors thus increases a caregiver’s negative psychological well-being due to depression, anxiety, stress, and poor sleep quality (Byun et al., 2016).

Sleep problems are increased in dementia caregivers due to caregiving stress associated with the duration of care and the stressors embedded in caregiving (Chuakhamfoo et al., 2020). Poor sleep quality is considered to be the crucial risk factor precipitating the caregiver’s negative behavioral and emotional responses that could, in turn, increase caregiving stress (Simón et al., 2019). Dementia caregivers experienced a greater sleep problem than others with chronic diseases (von Känel et al., 2012). Mills et al. (2009) also indicated that caregivers of older adults with moderate to severe dementia have more inadequate sleep quality than those caring for individuals with mild dementia. As a result, physical health problems such as metabolic and inflammatory changes, impaired glucose tolerance, weight gain, cardiovascular disease, and decreased cognition and function in dementia caregivers were reported (Fonareva & Oken, 2014; Okuda et al., 2019).

The Stress Process Model (SPM) viewed caregiving stress as a multidimensional stress process resulting in many different stress manifestations (Pearlin et al., 1990). Many recent studies indicated that NPs were associated with inadequate sleep quality of caregivers (Byun et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2014); a night-time disturbance, in particular, was the main reason for poor sleep quality for the caregiver (Liu et al., 2017). In addition, caregivers experiencing negative physical and mental well-being due to caregiving stress have worse sleep quality (Simón et al., 2019), and sleep quality was related to personal distress in dementia caregivers, although it was unclear whether the direction of this association was negative or positive (Smyth et al., 2020). While a systematic review implied that there were relationships between caregiver stress and sleep, caregiver samples were heterogeneous; they cared for the care recipients with dementia crossing stages of the disease (Byun et al., 2016). Another review of the literature also reported that there was inconsistency between caregiver stress and the sleep efficiency in the domain of sleep quality of dementia caregivers (Peng & Chang, 2013).

In Thailand, there is scarce evidence in the area of study on sleep in family caregivers of people with dementia (Chuakhamfoo et al., 2020), and few studies have examined possible differences in caregiving stress in relation to sleep quality, even though the number of people with moderate to severe dementia residing in the home is increasing. Additional research is still required to address the correlations between caregiving stress, viewed as a multidimensional stress process, and sleep quality in Thai dementia caregivers. In a recent study, Chuakhamfoo et al. (2020) called for the continued investigation of sleep quality and stress in Thai caregivers of older persons with moderate to severe dementia. Meanwhile, there is insufficient information pertinent to the relationship between caregiving stress and sleep quality in caregivers of older adults with dementia in Thailand. To explain the relationships between caregiving stress and sleep quality of dementia caregivers and to develop interventions in the future to improve sleep quality in these caregivers, this study aimed to explore the relationships between caregiving stress and sleep quality among Thai caregivers of older persons with moderate to severe dementia. We hypothesized that there was a correlation between high caregiver stress and inadequate sleep quality.

Methods

Study Design

A correlational cross-sectional study was employed to explore the relationships between the caregiving stress and sleep quality of family caregivers among older persons with dementia.

Participants and Setting

Participants were 72 family caregivers who resided together at the same home (e.g., spouses, siblings, children) who registered to care for older adults diagnosed with memory problems such as Alzheimer's disease and other dementias in the community long-term care (LTC) centers of two primary hospitals in the Songphinong district, Thailand. Caregivers eligible to participate in the study include those aged 18 years or older, caring for older adults with moderate to severe dementia for at least three months, and could communicate in the Thai language. Care recipients with dementia need to be scored in 2, moderate dementia, and 3, severe dementia, as assessed by Washington University Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) based on an assessment of areas of cognitive and functional deficits such as memory and orientation (Morris, 1997). The CDR scores were a part of the care recipient's clinical charts. Exclusion criteria were if participants were diagnosed with a stroke, cancer, heart attack, and mental health diseases such as psychosis or depressive disorder.

To compute the required sample size by the G*power version of 3.1.5.4, given α as 0.05, 80% of the power (Cohen, 2013). The effect size from related studies ranged from 0.40 to 0.65 (Al-Daken & Ahmad, 2018; Boostaneh et al., 2021; Simón et al., 2022). Therefore, the one-tailed hypothesis was considered based on SPM. Because there were rare numbers of moderate to severe dementia cases in the LTC centers in the Songphinong district, thus we used Lohr (2010) recommendation that a minimum sample of 50 was adequate to perform the study.

Instruments

A questionnaire addresses the demographic information of the caregivers. Its details included age, gender, marital status, relationship with the older person, education, care attendance hours, and length of duration.

The relative stress scale (RSS) was developed by Greene et al. (1982). This self-rated 15-item scale allows caregivers to express personal distress, social isolation, and negative feelings towards the care recipient. Using Brislin's method of translation processes, the researchers translated RSS from the original English version into the Thai language (Brislin, 1970). Three experts validated details of the content of the new version and rated the content validity index demonstrated with 0.92. The content then was back-translated to ensure that the translated version reflected the same contents as the original version. Scoring is rated from 0 to 4, with a total score ranging from 0 to 60. The higher the RSS score suggests higher stress of the caregivers. The total scores of < 25.7 were low stress, 25.8 to 34.2 was moderate stress, and > 34.2 was high stress (Ulstein et al., 2007). This scale presented reliability with Cronbach's alpha of 0.87 in this study.

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was created by Buysse et al. (1989). This scale was a caregiver's subjective measure to evaluate sleep quality and disturbances over one month. The PSQI comprised seven components: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. The total score ranges from 0 to 21 points. A score of 0 indicated good sleep quality, and 21 indicated severe difficulties in all areas. The higher the PSQI score indicates a lower quality of sleep. If the total scores were higher than 5, those indicated caregivers were poor sleepers. A Thai version of PSQI translated and back-translated by Jirapramukpitak and Tanchaiswad (1997) was used to measure a caregiver’s sleep quality with validity indexes of sensitivity of 77.78% and a specificity of 93.33%. A Cronbach's alpha reliability in this study was 0.84.

Data Collection

Data collection was carried out between August 2020 and January 2021. The Ethics Committee approved this study at Burapha University in Thailand. Flyers were distributed to recruit participants for the study; the village health volunteers passed on contact details of interested caregivers to the primary investigator (PI). The PI explained the study purpose, data collecting, and information about the right to withdraw from the study. All participants were given a choice to discontinue being in the study or refuse to answer questions at any time. Upon agreeing to participate, participants were invited to sign an informed consent form. In the multipurpose room in hospitals, the PI explained how to complete a demographic questionnaire, the RSS, and the PSQI questionnaires. Each participant was given an opportunity to fill out the questionnaires in private and spent around 20-25 minutes completing those questionnaires. The PI verified the completion of the questionnaires and asked participants if they missed some answers. If participants felt any questions in the item were upsetting, the PI did not continue to ask them.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 26.0 with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. There were no missing data in this study. Using descriptive statistics to analyze the demographic traits of the participants and describe caregiving stress and sleep quality, outliers were not detected. Normality on the residuals, linearity, and homogeneity of the variances were met. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were used to determine the correlations between caregiving stress and sleep quality for both total and subscales’ scores.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Burapha University, Thailand (No. G-HS 042/2563).

Results

Characteristics of the Participants

One hundred and fifty-eight dementia caregivers registered the official caregiver chart in the community LTC facility of two primary care centers. Seventy-two participants have met the study inclusion criteria and were voluntary to participate. The participants had a mean age of 50.82 years (SD = 11.99). Most of them were female (90.3%). Over half of caregivers were married status (58.3%), a son or a daughter (59.70%), and had a primary school education (70.80%). About one-half of them (59.30%) had a sufficient income to expense. Most participants had chronic diseases (65.30%). The average care duration was 13.20 hours per day, and the average length of care was 17.58 months.

Descriptive Characteristics of the Study Variables

Subscales and total mean scores of the RSS

From Table 1, the participants’ overall mean score of the RSS was 49.68 (± 4.71). The mean score subscale of the personal distress was 21.57 (± 1.60), the life upset subscale was 16.30 (± 2.22), and the negative feelings toward the care recipient subscale was 11.82 (± 2.18).

| Variable | Possible range | Actual range | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total RSS scores | 0-60 | 40-60 | 49.68 (4.71) |

| Subscales | |||

| Personal distress | 0-24 | 16-25 | 21.57 (1.60) |

| Life upset | 0-20 | 12-20 | 16.30 (2.22) |

| Negative feelings toward the care recipient | 0-16 | 5-16 | 11.82 (2.18) |

| Total PSQI scores | 0-21 | 5-20 | 12.43 (3.60) |

| Subscales | |||

| Subjective sleep quality | 0-3 | 1-3 | 2.26 (0.62) |

| Sleep latency | 0-3 | 1-3 | 2.75 (0.46) |

| Sleep duration | 0-3 | 0-3 | 1.80 (0.66) |

| Habitual sleep efficiency | 0-3 | 1-3 | 1.48 (0.97) |

| Sleep disturbances | 0-3 | 0-3 | 1.43 (0.55) |

| Use of sleep medication | 0-3 | 0-3 | 0.80 (1.13) |

| Daytime dysfunction | 0-3 | 0-3 | 1.88 (0.66) |

Note. RSS= Relative Stress Scale; PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

Subscales and total mean scores of the PSQI

As shown in Table 1, the participants’ overall mean score of the PSQI was 12.44 (± 3.60). In addition, the subscales’ mean score of subjective sleep quality was 2.26 (± 0.62), sleep latency was 2.75 (± 0.46), sleep duration was 1.80 (± 0.66), habitual sleep efficiency was 1.48 (± 0.97), sleep disturbance was 1.43 (± 0.55), use of sleep medication was 0.80 (± 1.13), and daytime dysfunction subscale was 1.90 (± 0.65).

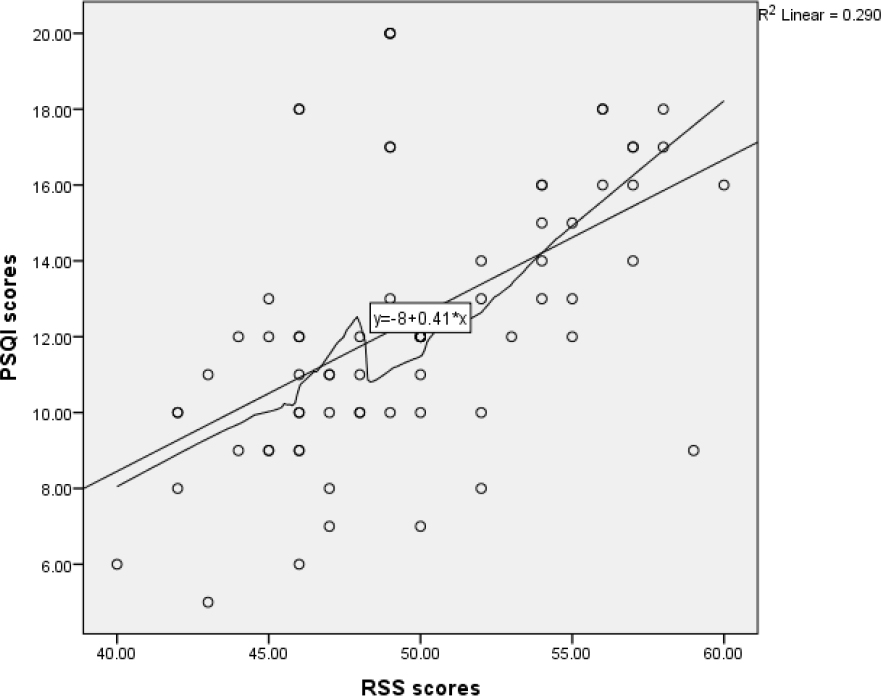

The relationships between the RSS and PSQI scores

Based on Figure 1, the scatterplot showed that the relationship between caregiving stress and sleep quality was positive and linear and did not reveal any bivariate outliers. We also tested and found normality in the residuals. The correlation between caregiving stress and sleep quality was statistically significant, r (70) = .539, p < 0.01. RSS scores were high (M = 49.680, SD = 4.710) and average sleep quality was increased (M = 12.440, SD = 3.595). The result of linear relationship suggests that for every one-unit increase in RSS scores, PSQI scores is expected to increase by approximately 0.411 units, β = 0.411, t(70) = 5.351, p < 0.01, Radj2= 0.280.

In addition, based on Table 2, statistically significant and positive relationships were found between subscales’ scores of caregiving stress (emotional distress r = 0.38, social life upset r = 0.42, and negative feelings toward the care recipient r = 0.46). However, the strength and magnitude of these relationships were moderate.

Discussion

This correlational cross-sectional study aimed to describe the caregiving stress and sleep quality of dementia caregivers and explain the relationships between caregiving stress and sleep quality. We found that participants endured caregiving stress and undesirable sleep quality. Participants had a high-stress level and a high level of personal distress, social life upsets, and negative feelings toward the care recipient. Thai family caregivers endured an average of 17.58 months for the length of care and 13.20 hours per day, which created a challenge to balance caring for their loved ones with family and work. The findings of our study have reinforced previous studies (Cheng, 2017; Chuakhamfoo et al., 2020; Shakiba Zahed et al., 2020). In addition, we found that dementia caregivers were poor sleepers, and they reported the poorest sleep latency and subjective sleep quality components. Managing NPs among their care recipients are regarded as a key stressor among these caregivers. They may be awakened by the care recipients who suffer from nocturnally disrupted sleep and night-time wandering. The findings from this study and previous studies affirmed that caregivers of older adults with dementia had severe sleep disturbances and chronic sleep problems (Chen et al., 2019; Chuakhamfoo et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2019).

Results of this study also found that caregiver stress in terms of its process was significantly and positively correlated with poor sleep quality. The findings of this study also indicated a large value of the effect size of positive relationship (r = 0.54). When caregiving stress increases, the unsatisfactory sleep quality of dementia caregivers is increased significantly. In addition, this study found that personal distress, social life upset, and negative feelings positively correlated with poor sleep quality. However, the magnitude of relationships between these caregiving stress domains and sleep quality were moderate. Family caregivers’ sleep quality may be disrupted due to personal distress or fatigue associated with role overload in caregiving. At the same time, the caregivers are disrupted due to nighttime care tasks related to nighttime NPs of the care recipient, in which caregivers perceive the increased negative feelings such as stress, anger, or anxiety (Song & Kim, 2021).

Moreover, family caregivers may not remember and manage the daily needs of the care recipient (Gao et al., 2019). This could be caused by the stress that makes falling asleep more difficult, impacting poor sleep latency and unsatisfactory subjective sleep quality components in dementia caregivers. The finding of this study is consistent with Simón et al. (2019). A strong positive relationship was found between caregiving stress and poor sleep quality, which is concordant with prior research (Al-Daken & Ahmad, 2018; Boostaneh et al., 2021; Greaney et al., 2022). Also, Adegbohun et al. (2017) and Smyth et al. (2020) supported that personal distress was the strongest correlation with positive direction to poorer sleep quality in caregivers.

In conclusion, the SPM helps provide an understanding of the caregiving stress process regarding the spread of primary subjective stressors for distressed caregivers leading to stress manifestations, which consist of caregiver's sleep quality. We found a large effect size on caregiving stress and sleep quality. Therefore, cause and effects should be explored in further study. An intervention to manipulate caregiving stress might be an effective strategy for improving their sleep quality.

Strengths and Limitations

This study is the first research to describe caregiving stress and sleep quality among the family caregivers of persons with moderate to severe dementia in Thailand. The SPM could help explain sleep quality in terms of physical and mental health in caregivers of older persons with dementia. The moderate strength and magnitude of association were found between overall stress, personal distress, social life support and negative feelings toward the care recipient, and sleep quality in caregivers. However, we conducted the study in one district in Thailand, which may have omitted relevant studies conducted in other settings and other countries. As a result, generalizability may be limited.

Implications and Recommendations

Nurses in primary health care need to assess and detect the health impacts of caregivers and their additional health risks affected by stress and sleep quality as early as possible. Also, they should develop interventions to decrease stress and improve sleep quality in dementia caregivers and deliver the interventions or programs to dementia caregivers. The community LTC facility integrated with the primary care hospital should consider providing the resources and supports to reduce caregiver stress. Further study should include caregiver participants of older adults with mild dementia and increase the sample size. Also, future studies should develop a stress reduction intervention to improve sleep quality in terms of the well-being of dementia caregivers.

Conclusion

Family caregivers of older persons with dementia highly manifested caregiving stress, resulting in poor sleep quality. Nevertheless, they managed the challenging care for their care recipients with long-term care. The findings confirmed the hypothesis initially proposed, allowing us to conclude the presence of positive direct relationships between caregiving stress and inadequate sleep quality. Therefore, nurses should refer dementia caregivers to an intervention or program as early as possible.