Background

Climate change negatively affects the well-being and mental health of people worldwide (Lawrance et al., 2021). More specifically, variable environmental temperature changes impact one's health and well-being, including health-related risks. Mental health, as defined in the Mental Health Act of the Philippines, refers to “a state of well-being in which the individual realizes one's own abilities and potentials, scopes adequately with the normal stresses of life, displays resilience in the face of extreme life events, works productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a positive contribution to the community” (Seventeenth Congress Republic of the Philippines, 2018). We put emphasis on resilience as part of the definition because a vulnerability exists among older adults on the impact of climate change since there are physical and physiological changes and possible limitations. The mental health and physical health of vulnerable groups, including the elderly, children, low-income, and disabled, were increased and/or exacerbated by situations related to weather events and the absence of disaster response actions based on a systematic review that included research conducted in a span of 12 years examining experiences that are natural disaster-related and psychological and physiological outcomes (Benevolenza & DeRigne, 2019). Climate change, including extreme weather, impacts a large portion of the population in various geographical areas with various threats to public health. Additionally, climate change affects directly exposed population groups and has increased vulnerability due to geographical conditions, access to resources, information availability, and protection (Cianconi et al., 2020).

As projected impacts of global climate change on behavioral aspect emanates from temperature changes, extreme weather, and rising pollution in the air. Due to the rising temperature, negative affect, interpersonal conflict, inter-group conflict, and possibly psychological distress increase (Evans, 2019). As one of the primary health professionals, nurses should prioritize pressing issues affecting the health and well-being of the older adult population. Given the nature of the phenomenon and its impact on the vulnerable population, including older adults, the limited understanding through research from a nursing perspective may have direct or indirect consequences on how nursing care is delivered. The continuous threats to their mental health, well-being, and risks and the delay in further understanding this phenomenon in the older adult population may lead to an adverse situation.

Worldwide, the older adult population accounts for 1 in 11 (703 million) people in the world over the age of 65, which is expected to increase by 2050 that 1 in 6 (1.5 billion) people worldwide are over the age of 65 (United Nations, 2019). In the Philippines, a person can be considered a senior citizen when they enter the age of at least 60 based on Republic Act 9994 (Philippines Fourteenth Congress, 2010). In the Philippines, almost 9.5 million of the total population were aged 60 and above in 2019, and projected to increase by 23.8 million by 2050 (HelpAge Global Network, 2019). It showed that by the mid-21st century in the Philippines, future climate projection affecting many parts of the country and throughout most seasons, the country is expected to become warmer with a multi-model ensemble mean increase of 1.2 Degree Celsius to 1.9 Degree Celsius, the projection is relative to a certain baseline period (Villafuerte et al., 2020).

Evidence showed that due to higher temperatures, there is an increase visits in to the emergency department for suicide, mental illness, and self-reported days of poor mental health. It was also reported that cold and hot temperatures reduce adverse mental health outcomes and increase them (Mullins & White, 2019). Six broad mental health outcomes were identified in a systematic review describing ambient temperature’s mental health effects. The mental health outcomes that were associated with the heat were (1) suicide; (2) bipolar disorder, mania, and depression; (3) schizophrenia; (4) organic mental health outcomes; (5) alcohol and substance misuse; and (6) multiple mental health outcomes/mental health service usages. There was also an increase in admissions and emergency department visits that are mental health-related due to higher temperatures (Thompson et al., 2018). In the course of the warm season, a 10°F or 5.6°C elevation in temperature was associated with increases in the risk for mental health disorders emergency room, suicide or self-injury, and intentional injury/homicide at varying degrees (Basu et al., 2018). Despite the available data from recent research, the richness of data from the experience of the older adult population on variable environmental temperature changes and their impact on mental health remains a gap. There is also a need to explore this phenomenon from a nursing perspective to add to the current conversation on mental health and temperature variations as a consequence of climate change. This study aims to explore and describe the experience of the older adult population related to temperature variations due to climate change and its impact on mental health.

Methods

Study Design

A descriptive phenomenology approach was used in this study because it reveals the true meanings of the key informants’ experiences. The researchers believed that descriptive phenomenology stimulates richness, breadth, and depth of their experience. This research design followed the three-step process that Spiegelberg (1975) outlined, including intuiting, analyzing, and describing.

Intuiting: this step is considered the first step in this research design. It is when the researchers become immersed in the experience being studied. In this phase, as much as possible, the researchers avoided an in-depth literature review, opinions, and other statements that might influence the interpretation of the phenomenon being studied. Instead, the researcher served as an instrument to uncover an accurate description of the phenomenon; Analyzing: in this step, the researchers made sense of all the data presented, including the relationships, connections, and clustering of themes as necessary. To do this, the researchers were immersed in the data by reading and re-reading the transcripts; Describing: this step covers communicating or writing down all the elements critical to convey an accurate description of the phenomenon being studied. To achieve the purpose of this phase, the researchers discussed the finding of the study using multiple angles.

Key Informants

We selected key informants from a city in Northern Luzon, Philippines, to participate in this study. The locale of the study was decided because the researchers were aware that there had been erratic environmental temperature changes in the area. Prior to the conceptualization of this study, before March-May 2021 and during pandemic lockdowns, there had been unusual complaints of variations in the environmental temperature. This triggered the researchers to explore this phenomenon in-depth.

To be included in the study, we set inclusion and exclusion criteria which include: (1) older adults (men and women) aged at least 60; (2) living in the city; and (3) able to give consent. The exclusion criteria used were: (1) impaired cognitive functioning; (2) inability to speak, hear or understand; and (3) psychosocial concerns. All the key informants who were invited to the study were eligible. The researchers employed purposeful sampling for this study. First, the researchers developed an online poster and distributed it to selected residents of the city. Key informants were then referred to either by their relative/s or acquaintances or themselves. Initially, we projected 10-12 key informants for this descriptive phenomenology study; however, data saturation was reached at n=11 participants because there are obvious similarities in narrative responses from key informants.

Data Collection

The researcher served as the primary data gathering instrument in any qualitative study. Open-ended questions emanating from a semi-structured interview guide presented in Table 1 were used to elicit broad responses from key informants. The semi-structured guide was developed initially by the researchers and received comments from internal reviewers from the university where the researchers are affiliated. Nevertheless, answers from previous responses were the basis for the succeeding questions. The English Version was translated to the local dialect to aid in understanding the key informants.

| Interview guide |

|---|

| Tell me about your experience with abrupt temperature variations. |

| How do you feel or think about this experience? |

| How do you see yourself having to experience this? |

| How did that experience impact you? Obligations? Relationships (family, friends, and community)? |

| How did you overcome that experience? What helped you? |

| How can you say in your own words this experience? |

Before the interview, the key informants were made aware of their right to withdraw from the study anytime they wished. In addition, key informants were informed that their responses would be recorded. Interviews were projected to be done using either a videoconferencing platform or a telephone interview; in this study, ten interviews were done using telephone interviews, while only one interview was done using a video conferencing platform. We used these data collection methods because, at that time, there was an increased number of individuals infected by COVID-19. Key informants’ health and safety were prime considerations.

With regards to issues in rigor in using these data collection methods, we relied on the richness of data and the truthfulness of the experience narrated by the key informants. Since an acquaintance referred the key informants, we assumed that their narrative responses were accurate and reliable. Data were collected between November-December 2021, while validation of the findings to selected key informants was conducted between January-December 2022.

Data Analysis

Data analysis took place immediately after each interview until data saturation was reached. The audio-recorded responses were transcribed verbatim. In the analysis of the transcript, Colaizzi (1978)’s seven-step phenomenological method was used, which includes steps on: After the interviews, we transcribed the audio recordings from all the key informants’ accounts of the phenomenon. We also used MAXQDA qualitative data analysis software (Trial Version) to store and analyze the transcripts. After files were uploaded to the software, we read the transcripts to fully grasp the key informants’ accounts of the phenomenon of interest. The transcripts were analyzed per participant. Coding was done through line-by-line examination of data while keen on the study's primary objective.

After the initial coding was done, we returned to the coded segments to ensure they were coded accurately. We were able to code sixty significant statements on temperature variations and mental health, while forty-one meanings were formulated from the significant statements. Important meanings were grouped into a cluster of themes using features of the qualitative data analysis software (MAXQDA). Next, we reviewed and reflected on the formulated cluster of themes to reveal the overarching patterns. Based on this reflection, the cluster of themes was aggregated into themes. We then developed a thick or detailed description for each theme and identified the overarching structure of the phenomenon. Finally, to validate the findings, we returned to selected key informants and disseminated the results to the community.

Trustworthiness/Rigor

In this study, establishing trustworthiness is vital to represent the experiences of the key informants accurately. Trustworthiness was observed through data saturation and thick description, enabling the findings to be applied in other contexts. Following Lincoln and Guba (1985)’s four evaluative criteria, such as credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability, trustworthiness was maintained.

Credibility was maintained by suspending our preconceived beliefs prior to data collection and suspending an in-depth literature review that may influence the interpretation of the findings, also known as bracketing, which is essential in conducting qualitative research. We did not read as many articles related to our study because we believe it may influence the depth of our analysis. Transferability was maintained by providing discussion at different angles and contexts. In the discussion of the findings, we used articles not only from nursing but also included articles from other disciplines. Dependability was achieved by validating the findings from individuals with the same characteristics as the key informants. We asked three selected participants to comment on the study findings. The findings were also disseminated in a community with the older adult population as participants. We gained insights during our discussion on them on the phenomenon of interest. Confirmability of the findings was achieved because the researchers kept an audit trail. We also presented the findings to the internal review committee of our university, where comments were received and incorporated.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the University of Northern Philippines-Ethics Review Committee with an approval number A-21-103. In the conduct of this study, the principles of informed consent, complete confidentiality, and anonymity were observed. Informed consent was observed by explaining the details of the research and their rights to participation. The agreement to participate in the study implies consent; the interview proceeded after that. Confidentiality and anonymity were observed using pseudonyms and codes in the transcripts. In the results, we also removed all possible identifying information of the key informants.

Results

Eleven key informants aged 60-77 participated in this descriptive phenomenology. The majority of the key informants were female (6/11), married (6/11), currently employed (4/11), and retired from previous employment (4/11). Additional details on their socio-demographic characteristics are presented in Table 2.

| Participant Code | Age (in years) | Sex | Marital Status | Number of Children | Employment Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 68 | Female | Widowed | 1 | Retired |

| 2 | 66 | Female | Married | 4 | Unemployed |

| 3 | 62 | Male | Widowed | 4 | Employed |

| 4 | 62 | Male | Married | 1 | Retired |

| 5 | 60 | Male | Married | 4 | Employed |

| 6 | 77 | Female | Widowed | 5 | Unemployed |

| 7 | 61 | Male | Married | 2 | Retired |

| 8 | 73 | Female | Widowed | 2 | Employed |

| 9 | 65 | Female | Widowed | 2 | Unemployed |

| 10 | 77 | Female | Married | 7 | Retired |

| 11 | 62 | Male | Married | 2 | Employed |

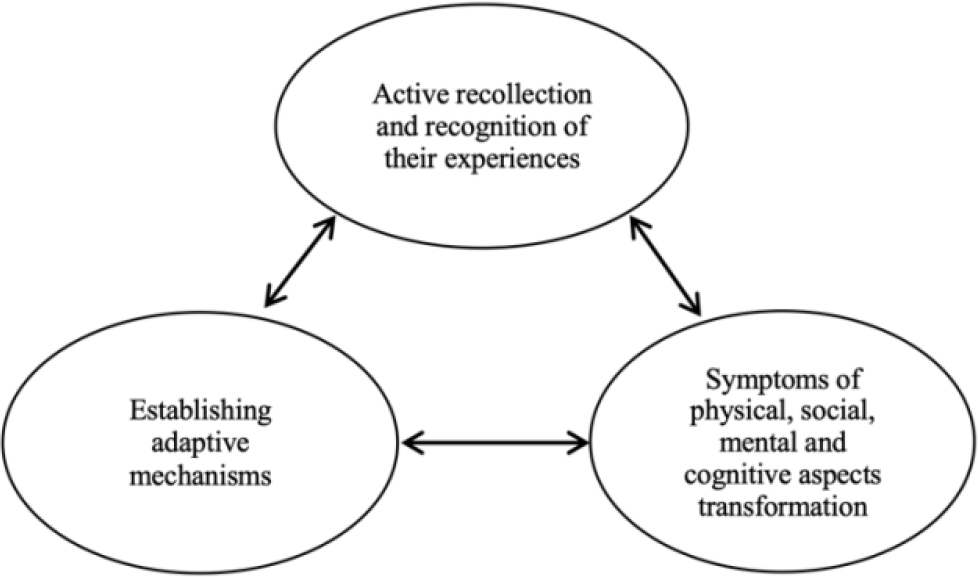

There are three major themes and seven sub-themes developed in this study, as presented in Table 3. The three major themes are (1) Active recollection and recognition of their experiences, (2) Symptoms of physical, social, mental, and cognitive aspects transformation, and (3) Establishing adaptive mechanisms. The major themes and their sub-themes suggest a process of recognizing the presence of the phenomenon, experiencing its impacts from multiple dimensions and establishing adaptive mechanisms, and showing resilient traits. These characteristics were developed over the years as they became experts in their physical body, mental aspects, and environment. Over the years, key informants might have gained experience, evaluated the experience, and established adaptive mechanisms by showing traits of resiliency.

| Themes | Sub-themes |

|---|---|

| Active recollection and recognition of their experiences | Understanding pre-existing experiences |

| Integration of the past and current experiences | |

| Symptoms of physical, social, mental, and cognitive aspects transformation | Perceived physical-related alterations |

| Social-related drawbacks | |

| Impact on mental and cognitive processes and health | |

| Establishing adaptive mechanisms | Redesigning lifestyle |

| Temperature variations resilience |

Theme 1: Active recollection and recognition of their experiences

This major theme reflects key informants’ conscious recollection and recognition of their experiences related to the phenomenon of interest. Based on their narrative responses, they responded to the current variations in temperature utilizing their experiences and knowledge readily available to them. Their recognition of past experiences may have helped them become more responsive to the current temperature variations. There was a natural connection to their experiences and responses. This major theme has two sub-themes: Understanding pre-existing experiences and Integration of past and current experiences.

The first sub-theme was formulated because key informants shared rich experiences on the phenomenon of interest in fine details. The sub-theme Understanding pre-existing experiences refers to the recognition or acknowledgment of the phenomenon, in this study, temperature variations. This understanding was developed over the years and became their knowledge base. They recall their usual activities and how they carry them out decades back under a predictable climate condition. Their previous experiences with temperature variations are very well incorporated into how they carry out their daily activities today. Participant 9 expressed her recognition of the current phenomenon by associating her experience with the increased vulnerability in acquiring viral infections: “The climate is not good; the risk of acquiring viral infection is higher today.” Understanding of the current phenomenon was manifested by Participant 10 by way of knowing that older adults are more vulnerable to the impacts of temperature variations: “We older adults may easily acquire cough and colds. It is very difficult to stay exposed in cold weather, so going out early in the morning is hard”. Participant 6 also shared her ways of recognizing the presence of the phenomenon: “During hot weather, you already know what will happen.”

The second sub-theme in this major theme is Integration of the past and current experiences. This sub-theme refers to the process of assimilating their previous and current experiences into one integrated knowledge base of knowing what has happened and recognizing the presence of temperature variations today. Comparing both experiences (previous and current) informed and heightened their awareness that the phenomenon of interest is a reality. Participant 8, when asked about the temperature variations, explained: “It is very far (before and now). Before during the month of December, it was very cold, but now it is very hot. This happened just recently.” Similarly, Participant 1 stressed the noticeable heat experienced during these times: “It is very different (referring to temperature variations). Before, you could even endure the heat, but now it is very hot.”

Theme 2: Symptoms of physical, social, mental, and cognitive aspects transformation

This major theme was formulated from key informants’ accounts of physical, social, mental, and cognitive transformations or perceived alterations from temperature changes. Their narrative responses indicate that temperature variations have triggered these changes. Some key informants also perceived that their current health-related risks were observed to appear with the occurrence of temperature variations. Temperature variations have limited their physical and social activities and, to some degree, produce changes to their mental and cognitive health or process of key informants. Three sub-themes that support the second major theme are: (1) Perceived physical-related alterations, (2) Social-related drawbacks, and (3) Impact on mental and cognitive processes and health.

The first sub-theme Perceived physical-related alterations refers to the felt physical changes and limitations that key informants experienced when temperature variations are felt or observed. For example, Participant 8 observed that when temperature variations are felt, she easily acquires cough and common colds: “The change in temperature, and when it’s hot, I usually have cough and colds.” Similarly, Participant 12 mentioned that exposure to outdoor hot weather resulted in colds: “For example yesterday, after going out for my check-up and got home, I observed myself having colds.” In addition, one of the health-related risks of the participants has been observed to appear. Participant 2 mentioned: “I feel like my blood pressure, if I am at home, I feel sick when the weather is hot.” Similarly, Participant 5 expressed concerns about his hypertension: “My hypertension is affected; it gets elevated.” Participant 3 said he experienced headaches because of the hot weather: “I got headaches when it is hot.”

The second sub-theme Social-related drawbacks refers to the social activities and interactions that have been disturbed or altered because of temperature variations. Participant 9 mentioned that the cold weather limited her activities and felt her body was heavier: “If the weather is cold, my activities are limited, and I feel that my body is heavier.” There was also a limitation on activities to earn for a living expressed by Participant 2: “We cannot go out (during hot weather) to earn for a living.”

The third sub-theme in this major sub-theme is Impact on mental and cognitive processes and health. It refers to the mental and thought processes either transformed, changed, or adjusted as they experienced temperature variations. Participant 8 explained that she is afraid of what is happening and mentioned: “It is very dangerous because if you are sick, it (exposure to temperature variations) may be aggravated.” Participant 9 explained that she becomes impatient and hot-headed because of the hot weather: “I feel impatient and hot-headed, and I can feel that my body is not okay.” Participant 2 expressed concerns about the impact of temperature variations on their children: “Our children are getting colds because of this climate change.” Participant 4 expressed fear of the noticeable change in the climate: “The situation is very dangerous and frightening because of the heat.”

Theme 3: Establishing adaptive mechanisms

This major theme refers to the processes involved in an attempt to establish adaptive mechanisms for temperature variations. There are two sub-themes under this major theme (1) Redesigning lifestyle and (2) Temperature variations resilience. This major theme was conceptualized as a reflection of the key informants’ accounts of how they adjusted their activities of daily living, ways of doing things, and coping, along with their experience of temperature variations. They explained that these adjustments were necessary as a means to accommodate the phenomenon.

Redesigning lifestyle is the first sub-theme under this major theme. It reflects the narrative responses of the key informants that they were able to implement measures as coping mechanisms with the experience of temperature variations. Some of the adaptive mechanisms narrated by key informants were behavioral changes such as the use of appropriate protective clothing during cold or hot weather, diet and water intake, and limiting outdoor activities during the hot season. Participant 2 expressed that she has been keen on taking her maintenance medication: “I drink my maintenance medicines during those times.” The role of the family members has been highlighted by Participant 6 to be significant in the adjustment of her daily activities as she experienced the phenomenon: “During cold weather, they do not allow me to wash the dishes and cook meals.” Participant 7 stressed the importance of adaptation to temperature variations: “If you do not adapt, it will give you stress.”

Temperature variations resilience is the second sub-theme uncovered under this major sub-theme. This sub-theme was formulated as a reflection of the key informants’ ability to do the things they usually do despite temperature variations. Key informants were still able to carry out their typical activities of daily living. They were also able to manage or be keen on their health-related risks as a response to temperature variations. Temperature variations resilience was manifested by Participant 11 through the resumption of work or activities despite temperature variations: “Even if I am on duty, we still do the work given to us.” Participant 4 showed resilience characteristics: “I am used to it (hot weather) because I used to live in the mountain.” Participant 7 narrated ways how he handled temperature variations: “I have clothes for cold and hot climates as well.”

Discussion

This qualitative study focused on older adults and their experience of temperature variation and its potential impact on mental health. Following Collaizi’s data analysis approach and the use of MAXQDA as a qualitative data analysis tool, 60 statements were extracted while 40 meanings were formulated, which led to seven sub-themes and three major themes. The themes and sub-themes reflect a mental or cognitive process of adaptation and/or resilience. The themes support the concept of adaptation because older adults were able to implement measures as a response to temperature variations and, at the same time, resilience because key informants resume their typical activities of daily living with significant adjustments. Figure 1 shows the process that represents the themes and subthemes. The cyclical shape indicates that it is a cycle since temperature variations are unpredictable. The figure starts with understanding the phenomenon, experiencing and perceiving its physical, social, mental, and cognitive impact, and finally implementing adaptive mechanisms through coping and showing resiliency characteristics. The bidirectional arrows in the figure represent the process that may go back or proceed to the next.

As the Mental Health Act (Seventeenth Congress Republic of the Philippines, 2018) is being rolled out in the Philippines and nurses as one of the identified mental health professionals expected to deliver mental health services, it is incumbent for nurses to explore areas where they can provide relevant and sustainable nursing care even at the primary prevention level. In this study, we focused on older adults and their mental health since the number is expected to increase, and older adults may have an increased vulnerability to unpredictable temperature variations.

Although various studies have been conducted on climate change among different population groups, there is a limited study among older adults. There are also limited nursing studies that delved into mental health and temperature variations. This study may add to the little understanding of how older adults have been affected by temperature variations in general and in the Philippines in particular. The Philippines, as one of the climate’s most vulnerable countries, should focus on mental health (Guinto et al., 2021). Additionally, Guinto et al. (2021) proposed expansion of the Philippines’ National Unified Health Research Agenda (NUHRA) (2017-2020) to include topics such as climate change consequences, climate-resilient, universal mental health systems, holistic and trans-disciplinary approach to mental health, sources of mental health resilience (individual, community & society), and nature-based solutions in relation to mental-wellbeing and climate change. The findings align with the proposed expansion of the Philippines’ NUHRA.

Moreover, the study findings were supported by qualitative research on knowledge and perception of health-related risks to health and protective barriers where participants have acknowledged that some medical conditions with heat may increase the risk in others. Participants have also reported that measures were already taken to counteract the effects of heat on them (Abrahamson et al., 2009). The findings showed that while key informants experienced temperature variations and expressed perceived physical, social, mental, and cognitive aspects impact, they were able to implement coping mechanisms and resume activities of daily living which may be comparable to the concept of resilience which is bouncing back after experiencing a shock (Adams et al., 2021). In a concept analysis on “resilient aging,” the antecedents were adversity and protective factors; the defining attributes were coping, hardiness, and self-concept. The consequence was the optimal quality of life (Hicks & Conner, 2014). Key informants in this study also experienced adversity and established their coping mechanisms. Although in this study, the difference between adaptive mechanisms and resilience was highlighted through the key informants’ narrative responses. Adaptive mechanisms relate to the behavioral and social adjustments implemented by key informants as a response to temperature variations. In contrast, resilience relates to the resumption of usual activities of daily living.

Without the intent to belittle their experience, the adaptation and resilience, two of the highlighted study findings, may have been strengthened by the strong family ties culture of Filipinos. Filipinos are known to be adaptive and resilient in difficult situations. Filipino culture appreciates the family, community support, and resource sharing to a person in need. The study findings showed that social support had a significant role in key informants’ quest for lifestyle adjustments and resilience as a response to temperature variations.

Implications of the Study

This study showed the mental or cognitive process of how older adults have implemented adaptive mechanisms as they experienced temperature variations. As nurses in the Philippines advocate for advanced practice roles, the study may illuminate advanced practice roles focusing on mental health among older adults in the community. Taking into consideration the findings of the study, sources and mechanisms of resilience among older adults should be further explored and strengthened through research and health promotion. Government, non-government organizations, higher educational institutions, and all stakeholders should collaborate in implementing health programs should be promoted. The inter-, trans-, and multi-disciplinary approach should be adopted since the phenomenon of interest of this study is not only limited to health concerns. Finally, we should take action on the urgency of outcomes of climate change as it affects health, well-being, and health-related risks.

Limitations of the Study

First, the process emerged in this study, including the mental health or process consequences of temperature variations, was based on the narrative responses of the key informants. The research design was a descriptive phenomenological approach which may limit the identification of confounding variables that may influence key informants’ accounts. Since eleven key informants took part in this study selected based on data saturation, generalization of the findings to other older adults in the locale of the study may be limited.

Conclusion

The themes in this study showed that the older adult population, despite their vulnerability to impacts of climate change due to physical and physiological changes, were able to develop adaptive mechanisms through experience and showed characteristics of resilience. The findings reflect an inherent process of recognizing the phenomenon, experiencing its adversities, developing adaptive mechanisms, and showing resilience characteristics. It also showed that the impact of temperature variations is multi-dimensional (physical, social, mental, and cognitive), which should be considered when developing programs to mitigate or prevent climate change’s impacts in general among older adults. This qualitative study also highlighted the acceptable difference between adaptation and resilience, which is social and behavioral adjustments or accommodation for the former and resumption of the usual daily activities for the latter.